Before they made it to the Oscars, the nominated films — not to mention all the films that didn't make the cut — were viewed by some 6,000 members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Many of those movies were shown in small, private, rented screening rooms all over Hollywood.

The studios have their own screening rooms, of course, but often directors want a more private place to screen works in progress — with no studio suits in sight.

Director-writer-producer Judd Apatow, whose films include Anchorman, 40-Year-Old Virgin and Knocked Up, says it's essential to have the opportunity to show a film three or four times to an invite-only audience. It's a mistake to show a film to the studio too soon, he says, "because if they don't like it, then they want to tell you how to fix it. We always try to make the cut good enough, so by the time they see it, it's already good and they're like, 'Nice job.'"

So as part of the creative process, Apatow and other movie-makers rent small screening rooms somewhere in town to show a rough-cut — an unfinished version — to a trusted handful of friends and family. "I want them to tear me apart and tell me the truth," he says.

Apatow relied on these small screenings for his latest comedy, Bridesmaids. Before Bridesmaids became a blockbuster, the film's first, small audience gathered in the Charles Aidikoff Screening Room, a Rodeo Drive establishment that many movie-makers use. It rents for $300 to $500 per hour, and for that price, you also get Aidikoff, who just turned 97.

At a recent screening for members of the Motion Picture Academy, Aidikoff grins as visitors grab handfuls of brightly wrapped candies en route to their seats.

"People say, 'Why don't you have popcorn?' " Aidikoff says with a laugh. "You know what I tell them? 'I'll get popcorn on one condition: That you stay after and you clean up.' Suddenly they don't want popcorn."

So instead he sets out little packages of Mars bars, Milky Ways and Red Vines. It costs $700 every two-and-a-half weeks to keep this Hollywood Halloween bowl filled, Aidikoff says.

As the audience settles into their seats, Aidikoff offers an introduction — and a few ground rules. "OK, folks, my name is Charles Aidikoff. This is my little establishment," he says. "This is what is known as a cellphone. It would be very nice if you all pushed the little button and turned it off."

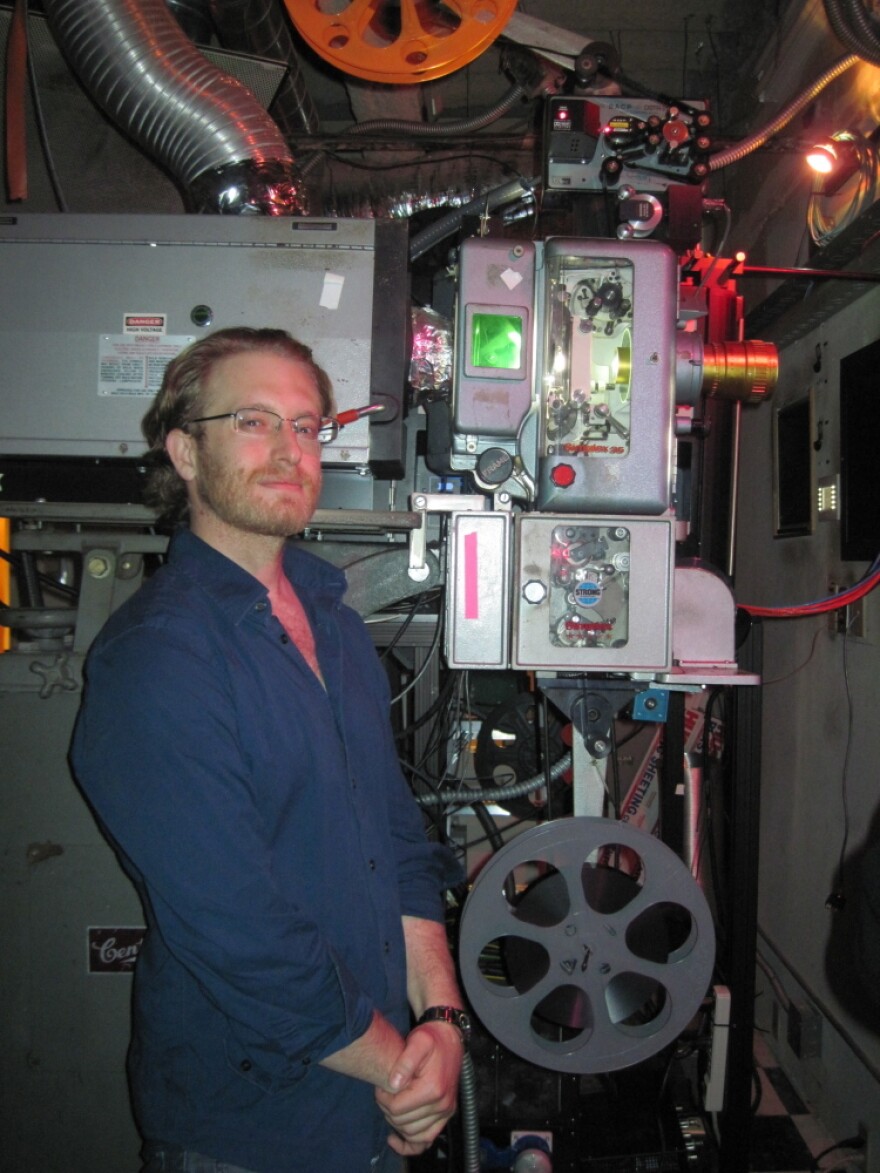

Up in the projection booth, Aidikoff's grandson Josh, who now manages the place, presides over a small, dark room that could match Dr. Jekyll's lab. Two huge projectors hold the hefty 35-mm reels of film. Each reel contains 2,000 feet of film — 15 or 20 minutes' worth. Tonight's movie — a press screening of a Chinese film called The Flowers of War — has eight reels. Josh and his assistant push buttons and switches on the wall to change over from one reel to the next. Every now and then, young Aidikoff peers out through a small window to make sure everything's OK on the screen.

"I've had several instances where film has ended up on the floor," he admits. "... Trying to put it back together again in the right order — that was a problem."

Four generations of Aidikoffs have been projectionists. A century ago, Charles' father, Max Aidikoff, ran silent movies in a theater in Coney Island. That's where his son Charles got the projection bug. At 97, Charles figures he has seen maybe 50,000 films. His son Greg worked in the booth for a while. Now, grandson Josh continues the dynasty. Josh learned it all from his "Pap" Charles.

"I was 12-and-a-half when I ran my first film for him," Josh says. At 15, he started running the films professionally. He still remembers Madonna's Evita — all 10 reels of it.

In this age of DVDs and instant streaming, one wonders about the future of screening rooms. The Aidikoffs have a big digital projector, too, but they think filmmakers will always want a safe place where they can show unfinished work to friends, and finished films to the press under perfect conditions. (You can rock in these seats without a single squeak.)

If it's up to Apatow, the Charles Aidikoff Screening Room will be around for quite some time.

"It's one of the great places; it's like a great deli," he says. "Sometimes you just love a deli [because of] that guy that greets you at the deli." He says Aidikoff's screening room reminds him of the deli his uncle owned in Bayside, Queens — only at Aidikoff's, he gets a movie instead of a hot dog.

With 57 seats, the Aidikoff Screening Room is like a miniature movie theater — but one where the people who make, review, star in and vote on movies can find a home in the dark for a few quiet hours.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.