More than 52,000 Americans died in the Vietnam War. Virtually all who survived came home with some level of emotional trauma. Decades after the fall of Saigon, thousands of veterans continue to live with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

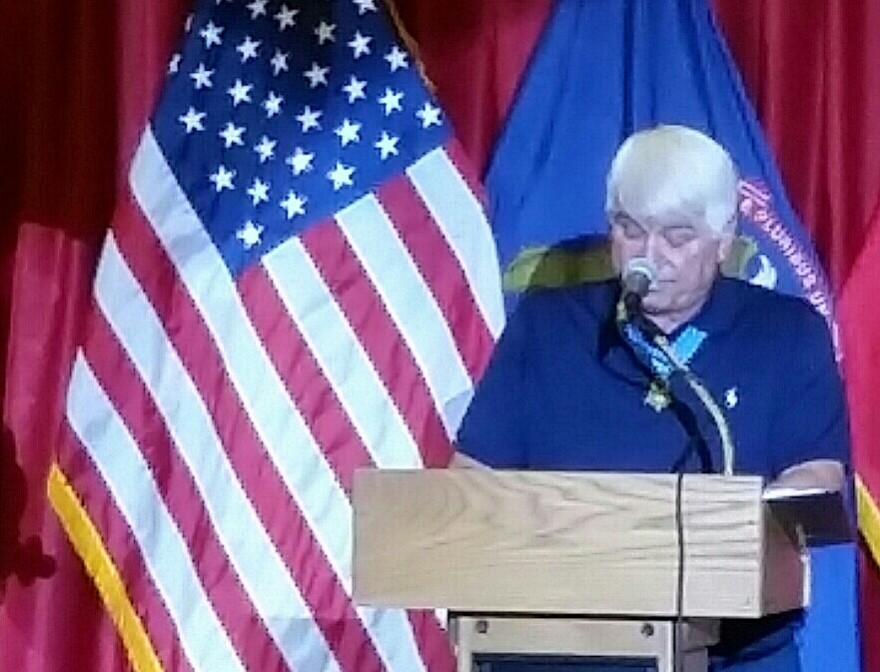

When Jim McCloughan spoke at a reception in his honor at the Michigan National Guard headquarters in Lansing, the former Army medic who saved 10 of his brothers in Vietnam revealed something that took him decades to discover.

More than 40 years after the terror of Nui Yon Hill, someone else stepped onto Jim McCloughan’s battlefield to come for him.

“He listened, and helped me walk through issues I had needed to confront,” says McCloughan. “I may have been able to save a few lives as a medic in Vietnam. But Brian saved mine.”

McCloughan is talking about Brian Gripentrog, a therapist with the Department of Veterans Affairs in Grand Rapids. When they met in 2011, McCloughan had recently retired from public education. For years, he’d been a workaholic. But not even a career teaching high school psychology could spare him from the flashbacks.

“Once in a while, you know...I’d get done with my next day’s assignment for the classroom, and it would try to sneak into my mind, but I’d go to sleep as soon as I could,” McCloughan says. “I did have nightmares. I just dealt with it; I put it in the back of my mind.”

So, what does it take to pull Post Traumatic Stress Disorder out of its hiding place and into a healing place?

“It’s a big question,” says Dr. Jeffrey Frey, a psychiatrist and a retired Army officer who served in the Michigan National Guard.

“My general approach first is basically convincing them that this can be treated, and it can get better,” he explains.

Frey says at the core of PTSD is the classic “fight or flight” response. He’s heard many patients talk about their desire to withdraw to a home on a quiet piece of land with a couple of dogs and no one else around.

“And that’s very common,” Frey notes. “Also, a phrase that I’ve heard over and over again almost verbatim is, ‘‘I just want to go back to combat. It’s the only thing that makes sense to me any longer.’ It’s a very stressful situation, no doubt, but it’s a stressful situation that they understand.”

Michael Berg was a field radio operator in Vietnam. He says he was known to keep his cool in combat. But like so many veterans, his mindset changed when he came home.

Berg explained it once in a public speech.

“I didn’t and still don’t feel or express emotions or love as you do, and I don’t trust others as you do. I am severely allergic to control, and I do not accept direction or advice from anyone unless I ask for it. My way has served me pretty good since the jungles of Vietnam.”

Berg tried outrunning and out drinking the war. Jobs and relationships came and went quickly. Then, in 2013, Berg was in a car accident that resulted in traumatic brain injury. It tripped a switch that brought Vietnam back to him.

Often, Berg resisted his treatment, chafing under regulations and bucking authority. In time, he and his caregivers developed a mutual respect.

Berg still does things his own way...but today, he sees the crash as a blessing in disguise.

Michael Berg still requires some treatment. But he’s already claiming a personal victory.

“I look at this experience as a success story, simply because of the determination, perseverance and ironclad resilience that I brought to this ballgame,” he says.

During that speech, Berg accidently knocked his plastic water bottle off the podium. He says 20 years ago, he might have thrown that bottle across the room in a fit of rage. But he just looked at it, calmly, and kept on going to the end of his speech.

That moment tells a lot about the journey of PTSD. Keep on going.

Find out more about "An Evening with WKAR: The Vietnam War" on Oct 5: